Remember The Chronicles of Narnia?

That’s how I felt when Jai Sovani-Garud first opened my eyes to Hindustani music theory. It felt like a small, simple doorway had been opened to reveal this massive, unique world that I had somehow never stumbled across over the course of years of arbitrarily wandering the internet for whatever extra musical knowledge I could get my hands on. Now this isn’t to say I had never heard or was not even familiar with the basics of Hindustani music and the theory behind it – I knew from years of listening to music and playing around on pianos that a flatted second scale degree had a sort of Indian Classical sound to it, but I never really knew why, and more importantly, I never knew how much more was out there.

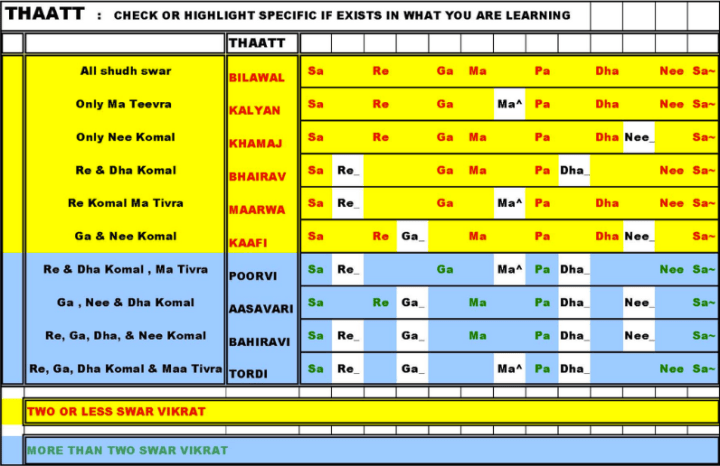

That is until Jai came in with the thaatt table. If you Google “thaatt” by itself, sadly the results will be limited to a sort of phonetic spelling of the word “that” as it’s said by someone with a classic valley girl accent in a YouTube video. In reality, a thaatt is essentially the same as a mode in Western classical music or jazz. Thaatt’s, however, are organized by their use of “swars,” which tell you which notes in the scale are altered. Additionally, they use a system very similar to the Solfege system used in Western music, but with different syllables, i.e. “Sa” would be the same as “Do.” In the thaatt table below, altered syllables are marked with either “_” for flat or “^” for sharp.

Hindustani Narnia does not end here, though. In fact, this is where it all begins. Thaatt’s are never actually performed straight up and down (just as you wouldn’t typically see someone perform a scale straight up and down), so these end up being the basis of a raga or improvised lines within a raga. I’ve included an example below of a Raga Bhairav – if you skip to about the 1:25 mark, you can hear him improvising using the syllables and he continues to do this on and off for a while.

What’s more is that these thaatt’s are not even everything. That’s right – there’s virtually infinite ways to use these scales, and Jai proved that tenfold while working with us. However, one of what I think is the most interesting applications is how strategically these thaatt’s are used in context of a performance. If you actually play each one on a piano, you’ll notice that the first one is essentially a major scale and that each one becomes increasingly more minor or dark sounding due to the flatted scale degrees and increased appearance of the augmented second interval, which is what gives Hindustani and Carnatic music their unique sound. This is no accident. In fact, these scales are used strategically during different times of the day. In the table below you can see which ones are used during which hours, and yes, this is a standard, although what this table doesn’t show is that the scales during the early morning waking hours are the more “major” sounding scales, and the later you get into the day/night, the darker and more minor the scales become.

You’ll also notice that there are scales on here not written in the thaatt table. That’s because, like I said, this is Hindustani Narnia, where the possibilities never end, which Jai proved to us as she began to teach us both a raga and some ways to improvise on it, more of which will follow in the next post!

What about this one – “leave your knowledge at the door.”

What about this one – “leave your knowledge at the door.”